Start the week #101

MADness, Inside Freedman Towers, Was Bartleby right? and a chortle or two

Greetings!

Sorry this is a day late. Or you could regard it as six days early. Happy belated Columbus Day to my American readers. But enough of this persiflage! On with the newsletter.

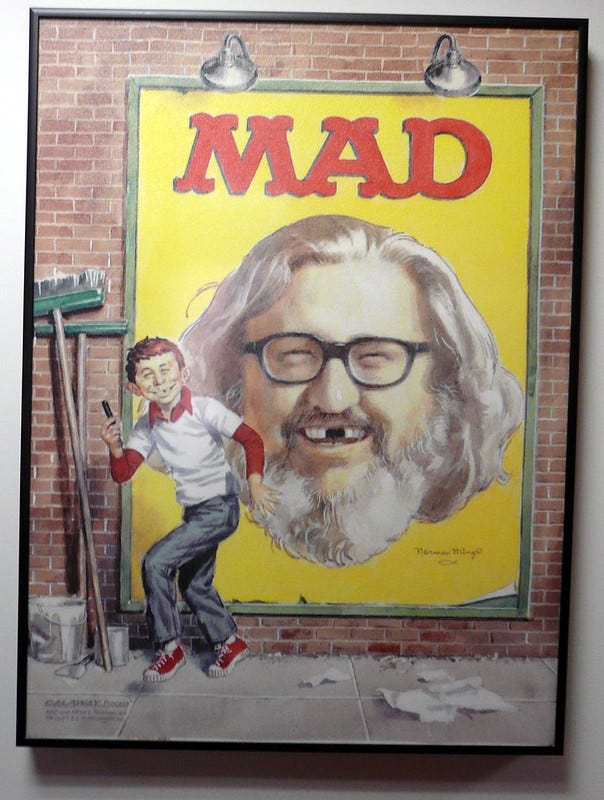

MADness

One of my favourite reads in my teens and 20s was MAD magazine. It was quite humorous, and took the rise out of just about everything, but in a gentle way, in contrast to the vituperative stuff that passes for satire these days.

For example, I saw the film The French Connection, and found parts of it quite hard to follow. As one does, I assumed the problem was me. Therefore I felt quite vindicated when MAD published a spoof of it called “What’s The Connection?”.

There were many regular features I turned to in each issue, one of them being Scenes We’d LIke To See. In one of these the writers came up with the idea of building adverts and lessons into TV programmes and films.

For example, the war movie:

Sergeant: OK, boys, let’s go.

Private: I can’t, Sarge. My stomach is killing me.

Sergeant: Stomach ache is caused by a build-up of acid. What you need is Pepticide. Pepticide has been developed by leading scientists to fight gastric acid fast. Here, take one.

<A short while later>

Private: I feel so much better now, Sarge.

Sergeant: That’s because Pepticide works fast, soldier. Now let’s get them dirty reds.

Another example: the Western.

Boy: Thank you, Sheriff, for killing Big Jake. Now we can all sleep easily in our beds.

Sheriff: I didn’t kill him, Son. What happened was that when I pulled the trigger, it released the hammer. Then the compressed spring drove the hammer forward. The firing pin on the hammer then extended through the body of the gun and hit the primer. The primer exploded, igniting the propellant. The propellant burned, releasing a large volume of gas. The gas pressure drove the bullet down the barrel. The gas pressure also caused the cartridge case to expand, temporarily sealing the breech. All of the expanding gas pushed forward rather than backward, causing the bullet to fly out1.

Boy: So thanks to heat and expanding gases, Dodgeville is now free of Big Jake?

Sheriff: Yep. That and the fact that I outdrew him.

All very chortlesome, but these days that sort of lecturing is a regular feature of TV programmes — at least in England. For example, I recently watched a series called Sherwood, which is a murder mystery that takes place against the miners’ strike in the 1980s. The situation affecting communities was very well depicted, but then in the final episode the programme makers couldn’t resist shoehorning in a lecture. In fact, not one lecture but two.

They weren’t flagged up as lectures, of course. They took the form of a couple of people speaking out in a meeting in a village hall, but that made it worse in a way. Perhaps it would have been better to have had a voiceover telling us what we were supposed to think and feel — at least that would have been more honest.

Thiis kind of thing reminds me of the Radio <country> I sometimes listened to in my youth. Quite often a man and a woman were having what was meant to sound like a genuine conversation, which invariably went like this:

Man: Well, Miranda, I’m so excited. The production of steel ingots has risen by over 50% since the last quarter.

Woman: That’s nothing, Darren. The production of chocolate has gone up by 200%.

etc

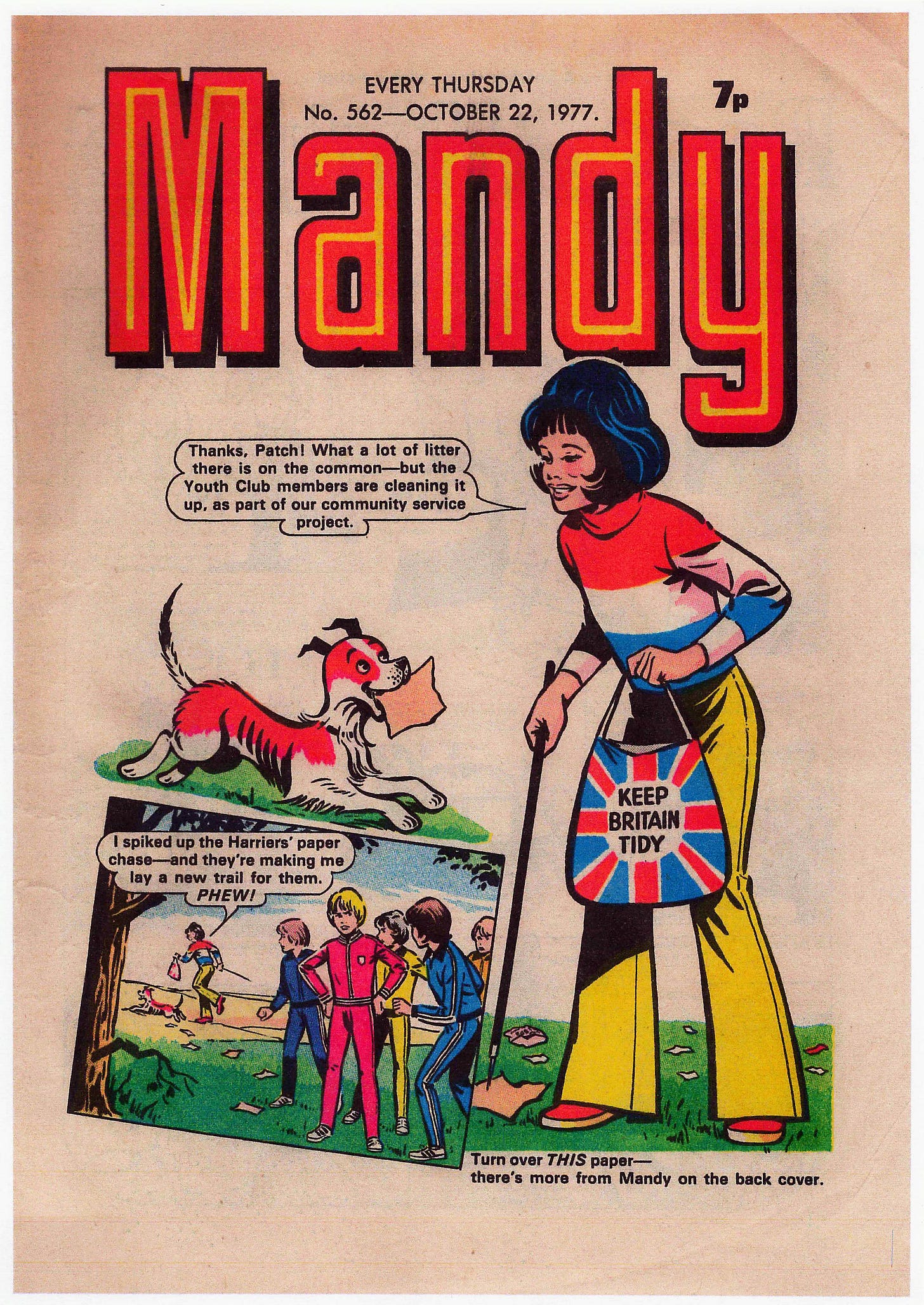

In other words, this is not a modern phenomenon. Indeed, when I was on a short holiday recently I bought a copy of a girl’s magazine called Mandy, which I somehow missed out on in my youth. In fact, I bought it for the sole purpose of illustrating this article because Mandy, back in 1977, seemed to be a real goody two-shoes who says things like “What a lot of litter there is, but we’re helping to clear it up.”. Another story ends with the girl saying something like “There’s nothing as important as friends and family.”

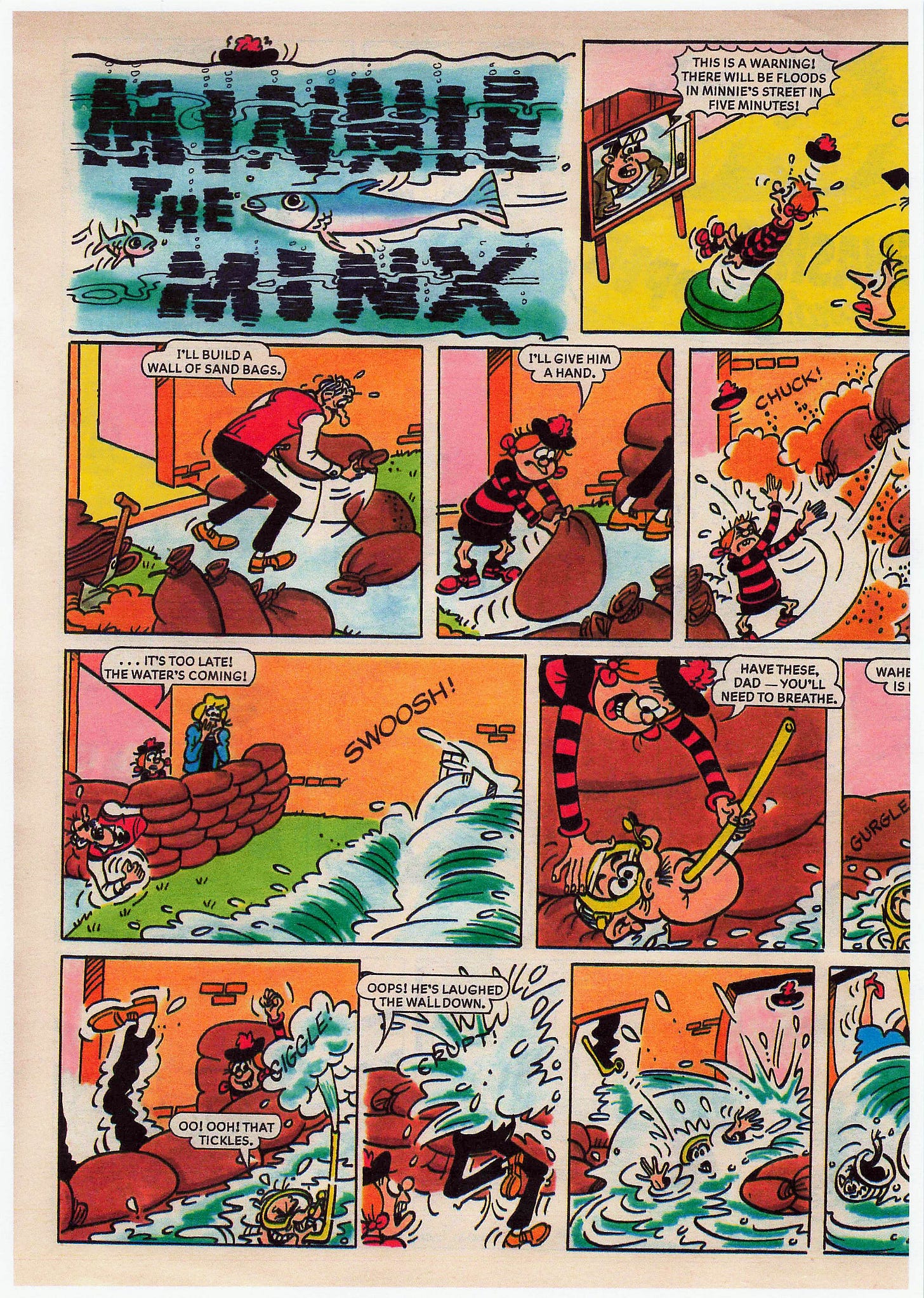

I mean, this was propaganda, and not even that convincing. I preferred girls who had a bit of the rebel about them, like Anne (see She Really Got Me) or Minnie the Minx in the Beano:

But it just goes to show: clumsy sermonising has been with us for a very long time.

Inside Freedman Towers

We’re having decorating done, and the only thing that keeps us going is constantly repeating to ourselves the Sufi saying, This too will pass.

Still, I suppose it could be worse. If I was doing the decorating, that would have been the after picture.

Was Bartleby right?

I like Bartleby or, to use his full name, Bartleby the Scrivener. He is the main character in a short story of the same name by Herman Melville. His standard response to any request, or indeed instruction, from his employer is, “I would prefer not to.”

This is perfect in its way. It is assertive, without being rude. Or at least not too rude. It may leave the other party wondering why or why not, but does not encourage any probing.

I’ve used it myself to good effect. A few years ago I reviewed a book in an education magazine, and although I recommended the book I had the temerity to refrain from saying “This publication alone justifies the invention of the printing press.” Cue outrage from the author’s assorted fans, and nothing supportive from the author himself.

Soon after that I started receiving emails from the author’s PR company asking if I would like to publish an article by him on my website. I didn’t see why I should act as his unpaid PR agent in view of the response to my review, so I simply replied to each request with, “Thank you for the opportunity but I would prefer not to”. After a while the emails stopped coming.

I first came across a Bartleby-like response soon after leaving my very first teaching job. A few days before my last one a sixth form girl (17-18 years-old) and I got chatting. I hadn’t taught her, in fact I don’t think I had even spoken to her before. But we seemed to get on well and decided to correspond with each other.

We exchanged a few letters in which we told each other what we were doing and how things were going. It was all very anodyne and then one day I received a letter from her saying, “I don’t want to hear from you any more”. I wrote to her to ask why not, and she replied, “I told you that I don’t want to hear from you any more.”

Quite brutal, I thought, and still do. Except that now I think, maybe she was right. Like the Royal Family: never explain, never complain. Fair enough: at least I knew where I stood, even if I didn’t know (and still don’t know) why I stood there.

I was thinking about this recently, when it started to become obvious that a person who kept saying they would love to meet up for a coffee, but never had a couple of hours to spare, had no interest at all in meeting up. Had they simply said, in respone to my umpteenth invitation, “I’d prefer not to”, the outcome would have been the same in practical terms, but I wouldn’t have felt like an idiot for having asked them several times.

I should be interested in what you think about this.

A few chortles

Articles I published elsewhere

I hope you’ve enjoyed this newsletter. That’s all from me for now.

Taken from https://science.howstuffworks.com/revolver2.htm

Of course I could respond to the Bartleby question, but I would prefer not to.

Okay, it works!

And MAD got me through youth. I could give you a link to my article on MAD, but I would prefer not to. This is habit forming.

I suspect that 6th form girl mentioned to someone that she was corresponding with a teacher and that all hell broke loose. They may have assumed you were ‘grooming’ her and told her to nip it in the bud. Obviously only a guess, but a definite possibility.

I think you’ve mentioned the ‘I prefer not to’ approach before. Hopefully this time I might remember it as it’s a handy fallback.

I could write more, but I’d prefer not to, so I’ll leave it at that. ☺️