This story was published seventy years ago — in 1954. Like all good science fiction, it’s still relevant today — perhaps even more so than when it was first published.

Ever since the idea of just-in-time inventories was invented, I have thought that ‘just-in-time’ was a bonkers idea. It makes sense only if you assume that there is never going to be a major event that will disrupt supply. I think that the 2019 pandemic, the war in the Ukraine and the situation in the Middle East have highlighted the folly of such assumptions.

Interestingly enough, and in quite a different context, my wife and I were discussing such assumptions yesterday. We were in one of those traffic situations where the top speed was around 5 mph and the most common speed was 0 mph. Despite the obvious fact that this behaviour would not shorten his journey by even a second, the motorist behind me was literally about an inch from my back bumper. Had our car conked out, he wouldn’t have been able to extricate himself. That was an everyday example of how an unforeseen (but not unforeseeable) situation could play havoc with your plans for the day.

The potentially devastating consequences of a drive for efficiency to the nth degree are shown in this science fiction story. In The Cold Equations, Tom Godwin posits the idea of a supply spaceship that has almost precisely the right amount of fuel for its return journey, taking into account weight and distance. What happens when the pilot discovers a stowaway on board?

I won't spoil the story for you for a few minutes by telling you (read it, especially if you’re a teacher and part of your job is to discuss moral issues with your students), but what a great starting point for a spreadsheet exercise! Can you construct a simple model showing what happens to fuel consumption when one of the critical factors (weight or distance) goes over a certain limit?

This activity can be enriched by asking students to do research into this area -- not necessarily in the area of space flight, but in the more accessible realm of fuel consumption by cars.

That’s what I did, and it proved to be a great exercise for the students because it was not only engaging from a computing point of view but also from an ethical one.

Spoiler alert

OK, here’s the big reveal. The pilot discovers from the instruments panel that there’s a stowaway on board. Armed with a gun, he demands that the stowaway shows himself. “He” turns out to be a young woman who thought it would be a good wheeze to hide on the craft in order to visit her brother on one of the planets having supplies delivered. The pilot contacts his superior to ask if there’s anything he can do, even though he knows that the answer is “no”. If the girl stays on board, the supply ship either won’t make it to the planet or will end up being stranded there. He has just enough leeway to allow the stowaway to have a tearful goodbye conversation with her brother before he has to eject her.

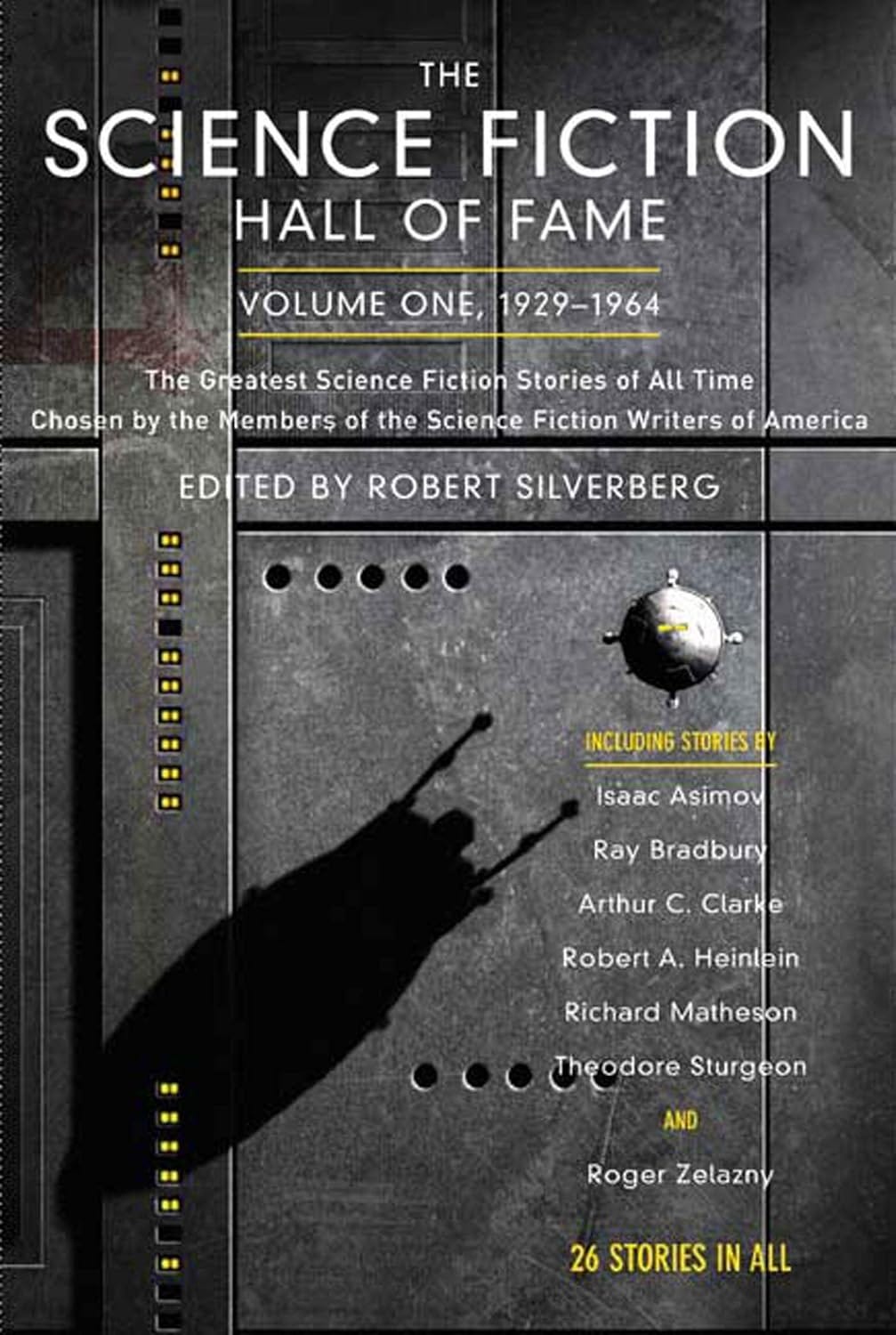

To be honest, I’m not entirely convinced that nothing else could have been done. As the tutor of a science fiction course I took at Imperial College, Glyn Morgan, said, you’d think the pilot might have been able to jettison a heater or something instead. Nevertheless, as a cautionary tale against never considering unintended consequences or the pursuit of efficiency to its absolute limit, I think this story works very well. You’ll find it in this volume:

Interesting discussion. I look forward to seeing readers' comments.

Just in time, just in case like a hoarder won’t let anyone go. But manna arrives by leaving supplies for the people and lightening the load leaving the girl with her sibling. I’m sure there’s a formula here about t/d=e. I’ll think about this. Let you know after I wake up and have my coffee.