Greetings!

The first part of this newsletter comprises a rather long article about good beginnings to articles. Then there are a couple of articles about tools I use. In one case it was to extract the text from a fifty year-old stencilled magazine. In the other it’s how I organise the resources for this newsletter and other blogs/newsletters I publish. As you know, I write and publish a lot; I need to be organised or it will all fall apart.

But enough of this persiflage! Let’s get to it.

Terry

Introduction

I have row upon row of books about writing. I have read all of them, sometimes only in part, but I have opened all of them and consulted them. I have reviewed a lot of books about writing. I have read a lot — a lot — of articles about writing. I have been on many — and I mean many — courses on creative writing.

I didn’t like that opening paragraph: too derivative (as you will see further on). So I am going to try again. Here goes…

Perhaps I’ve been reading the wrong articles, or the wrong writers of articles, but in my experience many nonfiction pieces open in such a boring manner that I have to force myself to read them. And only then if I feel I really ought to. I know I’m right. How many times do you see a magazine piece that cites great opening lines for nonfiction articles? How many times do you see a blogger or newsletter writer — such as here on Substack — ask their readers what their favourite nonfiction opening lines are? Exactly. I rest my case.

Article structure

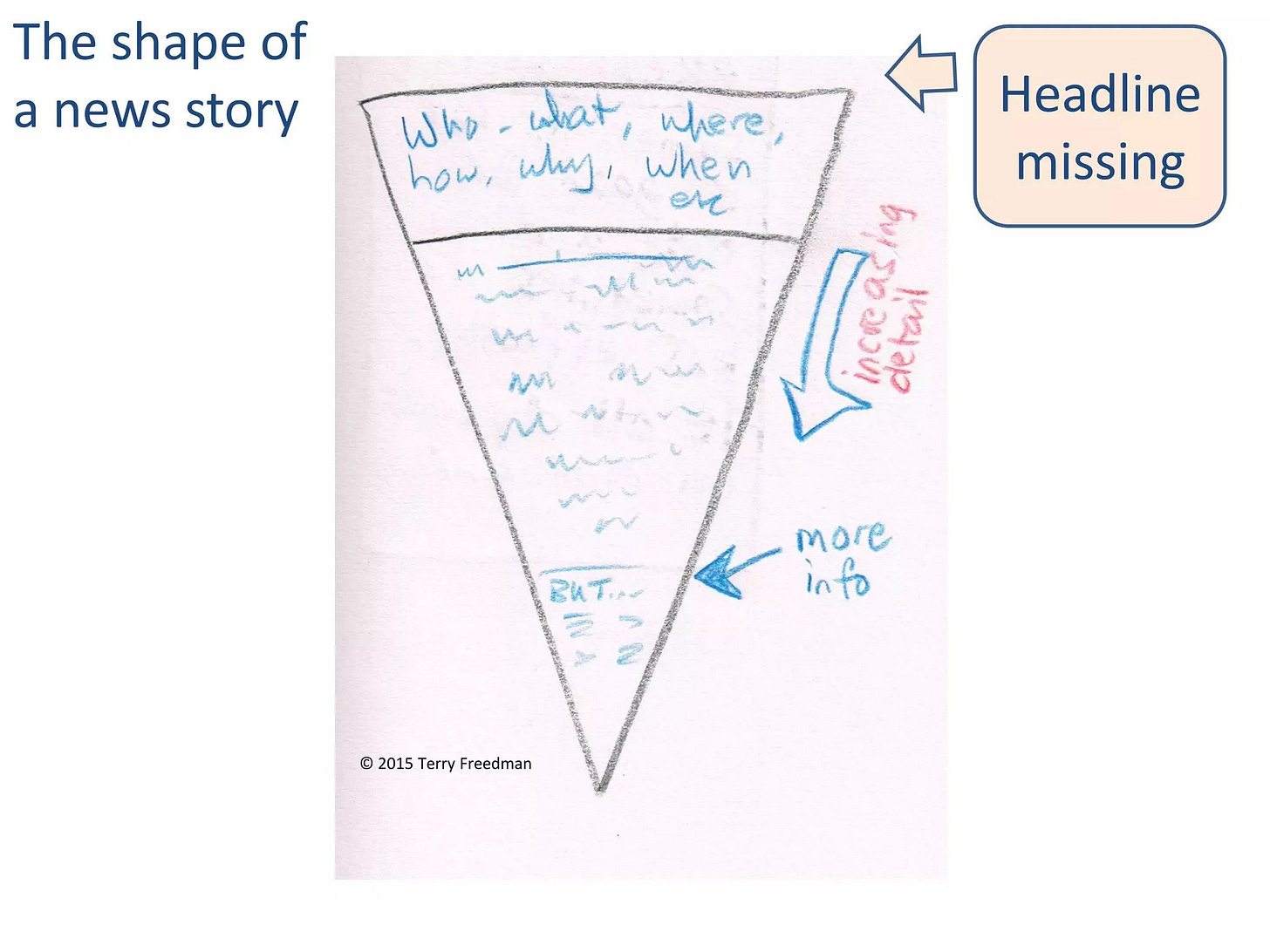

Look, one wishes to be fair. When it comes to news reports, writers don’t really have an awful lot of choice. The busy worker on their commute, or wolfing down breakfast before starting the day’s work, doesn’t have time for waffle and persiflage. They want the facts, and they want them now. That’s why newspaper news articles (as opposed to feature articles) tend to employ the inverted pyramid approach, which looks like this:

As you can see, all the meat of the piece is in the first paragraph. For example:

Fred Bloggs, the Housing Minister, has announced that a £1bn building programme will start in the new year.

That paragraph contains the bare bones, which is enough to enable you to decide whether or not you want or need to know more. In fact, if a newspaper is well-written you could obtain a reasonably good overview of the day’s news simply by reading all the first paragraphs1. As you go down the article, more and more fine details are revealed.

But feature articles are, or should be, different. They should make the reader want to read on — otherwise, what’s the point of writing them? Here are some examples of great beginnings, and why I think they’re great2.

Examples of beginnings

Panic at United as Mourinho gets his Trump cards ready

Giles Smith Saturday November 12 2016, 12.01am, The Times

This article appeared at the end of the week in which Donald Trump had won the Presidential election, and Jose Mourinho started as Manchester United Football Club’s manager.

The world awoke this week to discover the levers of power in the hands of a man with perceived demagogic tendencies and to find significant decisions about the future resting on the whim of an acknowledged egotist who has threatened to undo everything his predecessor has put in place. Little wonder Manchester United fans are worried.

I love that because, despite the fact that the article appeared in the Sports section of The Times, and the headline clearly names Mourinho, we’ve been led to believe, or the writer has allowed us to believe, that he’s referring to Trump. So the last sentence comes as a ‘Gotcha!’ which makes you laugh and makes you want to read on, if only to discover if the new manager can really be that bad.

It’s also humorous because of the hidden hyperbole: was the world really concerned about who’s taken over as the manager at Manchester United? Most people in England, let alone the world, couldn’t have cared less!

History, totally destroyed

By Crispin Sartwell, New York Times, Nov 11th, 2017

Like many top intellectuals the world over, I’ve been thinking about the shape of history itself.

This is a wonderful opening sentence because it’s obvious that unless the writer has an ego so large it has to be transported around in a shopping trolley, he is joking. It’s a good way of signposting to the reader what sort of article this is likely to be: humorous, though perhaps with a hint of truth, by someone who doesn’t take himself too seriously, or perhaps is having a subtle dig at those who do. As a man who spends a lot of time solving the world’s problems (while doing the shopping or feeding the feline layabouts who occupy our home) I just had to read the rest! (The writer’s theory is that rather than history being determined and driven by “great men”, a more likely candidate for progress would be the Jackass Theory or The Colossal Bungler Hypothesis. Sounds about right to me.)

To the Innards of the Earth: Review of Underland: A Deep Time Journey By Robert Macfarlane

By Jonathan Meades

If I were a shrink, I’d worry about Robert Macfarlane – his dicing with eschatology, his claustrophilia, his recklessness, some of the company he keeps (sewer punks, cavist ultras, grotto mystics). But I’m not: I’m merely a repeatedly delighted fan of a true original. Macfarlane is a poet with the instincts of a thriller writer, an autodidact in botany, mycology, geology and palaeontology, an ambulatory encyclopedia – save that much of the time (a dodgy word in this context) Macfarlane does not ambulate but hauls himself feet first through tunnels the circumference of a child’s bicycle wheel in absolute darkness where day, night, maps and GPS do not exist.

Isn’t that a great opening? The first part of the first sentence suggests that Meades thinks Macfarlane needs psychiatric help. Then there’s a run of several words that most of us (OK, I) have to look up in the dictionary. Plus the marvellous description of the author as being am ambulatory encyclopedia, which is rather more original than the more familiar “walking encyclopedia, even though the two expressions mean the same thing.

I do have a soft spot for lists, by which I mean words and phrases that roll on and on and thereby have a sort of mesmerising effect on the reader. They carry you along and you don’t want to stop. You’ll see this again in the Foster Wallace example. I also like the fact that Meades makes us sing for our supper: it’s not exactly an easy read, but how much more rewarding than the more prosaic “This is not bad. I’ll give it five3.”

Frank Sinatra Has A Cold

By Gay Talese, May 14th, 2016.

Frank Sinatra, holding a glass of bourbon in one hand and a cigarette in the other, stood in a dark corner of the bar between two attractive but fading blondes who sat waiting for him to say something. But he said nothing; he had been silent during much of the evening, except now in this private club in Beverly Hills he seemed even more distant, staring out through the smoke and semidarkness into a large room beyond the bar where dozens of young couples sat huddled around small tables or twisted in the center of the floor to the clamorous clang of folk-rock music blaring from the stereo. The two blondes knew, as did Sinatra's four male friends who stood nearby, that it was a bad idea to force conversation upon him when he was in this mood of sullen silence, a mood that had hardly been uncommon during this first week of November, a month before his fiftieth birthday.

I don’t know about you, but I can see the bar Sinatra and his entourage are in. I can feel the taut atmosphere. I want to know why Sinatra is in a “mood of sullen silence”. I am compelled to read on.

How does Talese achieve this? I think the title of the article does a lot of work. Were I to write an article here called Terry Freedman Has The Sniffles, most people would say (rightly, in my opinion) “so what?”. But for a singer to have a cold could be a pretty devastating event. As Talese goes on to say,

Sinatra with a cold is Picasso without paint, Ferrari without fuel—only worse.

I also think there is the relentless detail, much of which serves to raise more questions than answers: who are these blondes? What friends? Why are we being told all this?

If you do nothing else today, read that article. It’s a seminal piece of journalism, absolutely full of detail4.

Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise

This essay by David Foster Wallace from January 1996 is also known as A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again. It’s probably his most well-known nonfiction essay. Here’s how it starts:

I have now seen sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. I have seen an all-red leisure suit with flared lapels. I have smelled suntan lotion spread over 2,100 pounds of hot flesh. I have been addressed as "Mon" in three different nations. I have seen 500 upscale Americans dance the Electric Slide. I have seen sunsets that looked computer-enhanced. I have (very briefly) joined a conga line. I have seen a lot of really big white ships. I have seen schools of little fish with fins that glow. I have seen and smelled all 145 cats inside the Ernest Hemingway residence in Key West, Florida. I now know the difference between straight bingo and Prize-O. I have seen fluorescent luggage and fluorescent sunglasses.

This is compelling, and we can approach it on three levels.

Firstly, the structure. There is the repetition of the phrase “I have…”. This is reminiscent of Georges Perec’s I Remember, which is a relentless list that includes sentences on a widely disparate range of topics5. Again, it carries you along.

Then there are the contents of the list, which one suspects Foster Wallace is less than impressed by. After all, knowing the difference between Bingo and Prize-O does not sound to me like the pinnacle of human knowledge; joining a Conga line is something I have done once, drunk on happiness rather than wine, and which I’m very happy to not do again even though it was reasonably enjoyable at the time.

And finally there is the words “hot flesh”, which has completely different connotations to the word “skin”. Face it: it sounds gross.

Who could not continue reading after that opening?

Concluding remarks

I hope you have found this essay interesting. Have any of these examples appealed more than others? Do you feel encouraged to be more adventurous or imaginative in your own essay openings? Do tell.

Coming up:

How I extracted the text from a fifty year-old typewritten document. Also, news about a new Experiments in Style Extra section for paid subscribers. Plus one of the ways in which I organise my material for my writing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Eclecticism: Reflections on literature, writing and life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.