Series, Sequence, Stagnation in Quicksand

A structural analysis of the novel

You may find it useful to read Use a spreadsheet for literary criticism before reading this one.

One of the ways in which I tend to evaluate or at least think about a work I read is to consider what feeling it has left me with. I realise that this is not the most intellectual way of approaching literary criticism, but I have found that for me it’s the best way in. That is because once I have identified that core feeling, I can then begin to think about what the author has done in order to bring that about.

The feeling I had when I reached the end of Quicksand was a sense of stagnation. I thought at first this couldn’t be right, because the novel certainly didn’t feel stagnant while I was reading it. In fact, there was quite a lot of events and a great deal of very vivid description, so where had this feeling of stagnation come from?

As it happens, I have recently started reading a book called If Not Critical, which consists of lectures given by Eric Griffiths. Griffiths was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, as well as a broadcaster. According to his obituary in The Times, he was a “literary critic known as ‘Reckless Eric’ whose catty, acerbic lectures were listed in the entertainment section of the student newspaper”.

In one of his lectures discussing timing, Griffiths draws a distinction between a series and a sequence, and it struck me that his analysis could be applied to Quicksand. Here’s what he says [paraphrased]:

“Human experience takes place in time; our experiences therefore form a series. …Our experiences may also form a sequence as well as a series.

A ‘sequence’ is a pattern of significance which unfolds in time but in which ... meaningful occurrences which are separate in time are related to each other.

A good example of this distinction between ‘series’ and ‘sequence’ is a poem. In any decent poem, it will matter that line two comes after line one and before line three; this is the series of the poem. There will also be points of contact between lines two, five and sixteen, … (perhaps because they each contain a ‘flower-image’, or a similar cadence at line-end or whatever); this is the sequence of the poem.”

Example

Savings Blues

By Irving Fischer and the Classicals

You know I woke up this morning, and saw that interest rates are way too low

I said woke up this morning, and saw that that interest rates are way too low

I said to my woman, I ain't gonna save nothin' no more

My woman told me, I oughtta stop spending my cash

Yes my woman told me, I gotta stop spending my cash

I told her interest rates are low, so ain't no point in buildin' up a stash

One of these days, interest rates are gonna rise again

Yes I got a feeling, that interest rates are gonna rise again

When that day comes, my days of spending are gonna end

Series:

I woke up.

I noticed interest rates.

I spoke to my woman.

She spoke to me.

I’m planning what I’ll do when things change.

Sequences/themes:

Interest rates.

Saving/spending decisions.

What happens when we apply this framework to Quicksand? I broke down the novel into a series of events, boiling each of them down to their bare bones. Here’s what emerged, in the order in which they occur, and drawing on Larsen’s descriptions as far as possible[1]:

1. Although Helga felt “joy” and “zest” when she started working at Naxos, two years later she hates it, and feels that her “personality has been smudged out” and that she must go now (“she longed for immediate departure”). [p5]

2. James Vale is almost collateral damage. They connected because they were both new and lonely, they “drifted into a closer relationship” and became engaged [p7]. Two years later she thinks the effort to fit in has been wasted, and wants to be unengaged. [p8]

3. She almost fled from Mrs Hayes-Rore (“perhaps she’d better turn back”) but changed her mind. [p40]

4. In Harlem she was “contented and happy” [p46] but then she starts to “draw away from those contacts which had delighted her”[p47], and even Anne begins to distress her. [p48] She lays “for long hours thinking self-accusing thoughts” and feels she has to get out.

5. She goes off to Copenhagen [p63], where she is happy at first, but then starts to feel an “indefinite discontent” [p81].

6. She also comes to detest the artist, Olsen.

7. She begins to “welcome the thought of returning to America” [p92] and eventually does so. At first she loves Harlem, but starts to feel the urge to return to Copenhagen [p96]. However, she gets married instead [p117].

8. She is excited and driven at first [p123], with several projects in mind. But then she starts to “want to escape” [p135].

9. She doesn’t leave but embraces religion instead [p126]. After a while, however, she becomes “disillusioned” [133].

10. Finally, even though the novel ends on a bleak note: she is having her fifth child and so is, we assume, tied to that life forever, there is a distinct possibility that she will go. She wants “to not leave the children – if that were possible” [p 135].

Breaking down the novel into these basic elements, it seems to me that Helga has not had nine or ten experiences. Rather, she has had the same experience nine or ten times. It is this fact that imbues the novel with the sense of stagnation. To use Griffiths’ framework, there has been a series of nine or ten events, but only one sequence.

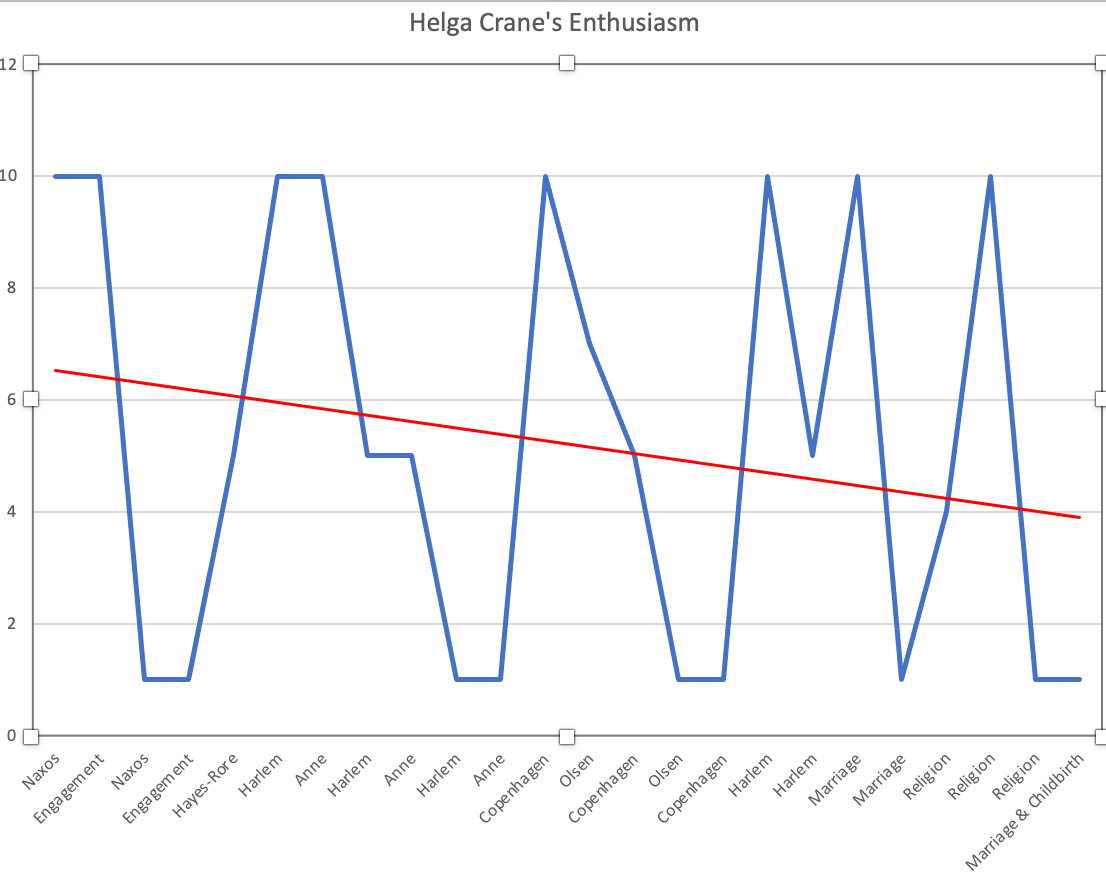

Here is a graphical representation of this state of affairs. I have assigned values to each episode. The numbers mean nothing in themselves, only in relation to each other.

Interestingly enough, a similar conclusion is reached by Anne E. Hostetler, though by a completely different route. In a paper entitled The Aesthetics of Race and Gender in Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, she writes:

“Unable to bear the thoughts she can no longer suppress, she [Helga Crane] suddenly disrupts the illusion of aesthetic harmony in the opening tableau … by turning on the overhead light and stuffing her teaching materials into a trash can. Thus Larsen sets in motion a dynamic that is repeated throughout the text. Time and again Helga finds herself trapped in a particular social setting and responds with flight, desperately seeking a place where she can live without hypocrisy. Structured as a journey, the novel appears to critiize the narrative closure of the journey motif…”

From a psychological point of view, we could say that Helga Crane’s problem is that no matter where she goes, she takes herself with her.

Finally, and again from a completely different perspective, Nicholas Royle discusses the nature of quicksand itself. He writes:

“Quicksand— I am talking about the thing, the sandy watery stuff, literal and figurative, textual and real—quicksand is inextricably involved with the idea of being swallowed up or buried alive. You step into it, you find yourself in it, you ought to know not to panic, you have to have courage, but what is happening, if you are not fortunate, is that you sink, you are sinking not just in the quicksand of your thought … but your body sinks and sinks,”

To my mind, nothing embodies stagnation more than being literally physically stuck in a substance beyond your control.

In conclusion, whether one approaches the novel by looking at its basic structure, or viewing it through the lens of race and gender as Hostetler does, or by scrutinising the meaning of the title as Royle does, I would say that a primary theme of the novel, if not the main theme, is stagnation.

References

Griffiths, Eric and Johnston, Freyer (Ed), If Not Critical, 2018, OUP

Anne E. Hostetler, The Aesthetics of Race and Gender in Nella Larsen's Quicksand, PMLA ,

Jan., 1990, Vol. 105, No. 1, Special Topic: African and African American Literature (Jan., 1990), pp. 35-46

Nicholas Royle, Quicksand, Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal , December 2018, Vol. 51, No. 4, A SPECIAL ISSUE: LIVINGON (December 2018), pp. 67-82

[1] I am using the version published by Serpents Tail: ISBN 978 1 84668 785 3